Criminal justice and the technological revolution

The journey towards a fully digitally-enabled criminal justice system is underway and the potential benefits are vast. The work yet to do is daunting, but the increased access to justice it could deliver is exciting.

The acceleration of digital and virtual justice

COVID-19 has prompted a profound shift in the use of technology across justice systems internationally. In the countries our global initiative focuses on – Australia, Canada, India, Ireland, Netherlands, the UK and the US – and indeed across the world, police, prosecutors, courts, prisons and probation or parole services increased their use of video-conferencing and remote working significantly. In England and Wales and states or provinces of Australia and Canada, preliminary court hearings (dealing with procedural matters before trial) became almost entirely virtual affairs. The e-committee of the Supreme Court of India has been regularly reporting on new virtual initiatives in high courts across the country, including e-filing, virtual training, and automatic case update systems.1 Prisoners in most countries were given greater access to video calls to maintain family contact and liaise with lawyers, including occasionally through in-cell tablets. And probation and parole officers shifted from inperson meetings with those released from prison to a mix of phone, video and socially distanced in-person check-ins depending on perceived needs and levels of risk.

The impact of these changes still needs to be evaluated, but this remains a profound shift. And in many cases, COVID-19 responses either accelerated or complemented longer-term initiatives to digitise large parts of the criminal justice system. Our work shows that our focus geographies all have major programmes of technology-enabled change underway to digitise and manage criminal case information through online platforms and to increase use of remote and virtual working technologies. Many involve long-term billiondollar investments and are among the most significant change programmes operating across governments.

Digital and virtual justice at a crossroads

The challenge today is how to build on and accelerate recent progress. As one justice leader observed, “The pandemic has provided support, drive for digital transformation…[It’s been an] interesting time to find the places to accelerate digital transformation – putting in some interim solutions, while keeping in mind that there is a wide range of transformation that will require more investment in time and business thinking”.2 Our interviews with criminal justice leaders suggested that COVID-19 responses had increased enthusiasm about the benefits of technology, as well as optimism about what was possible. As one Canadian police chief put it, “it comes back to the COVID factor and economic costs. Government is stretched. That has created a platform for digital solutions, [and potentially] exponentially reduced the costs of court and corrections systems – game-changing”.3

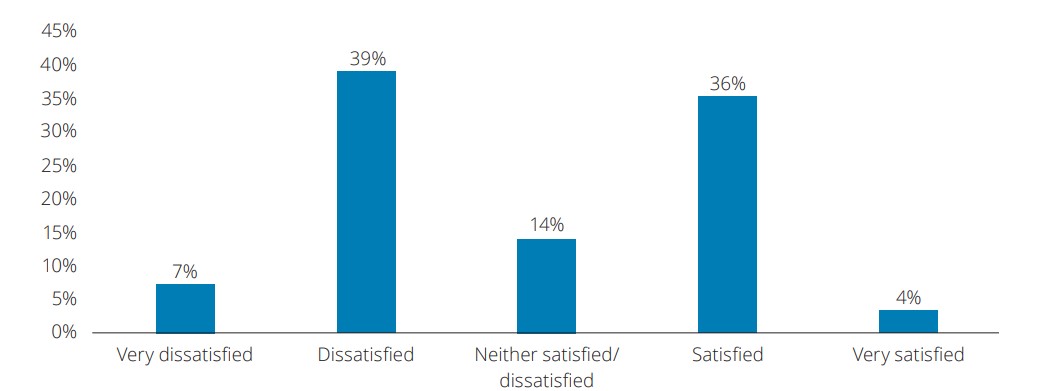

Many governments, for example Ireland and British Columbia, Canada, have justice ministers who have put digital transformation at the heart of their reform agenda. And a degree of optimism at least is reflected in the results of our global justice leader survey. As recently as 2019, the Chief Justice of Ontario, Canada – now leading a range of digital justice reforms – was noting that some courts had very poor WiFi access or even none at all.4 Similar laments were heard across the world. But our survey showed that in the autumn of 2020 nearly as many justice leaders were satisfied with their justice systems’ use of technology, as dissatisfied (figure 1)

Figure 1: Satisfaction with technology adoption Q. How satisfied are you with how the criminal justice system in your geography is performing in adopting technology effectively?

Source: Deloitte survey of justice leaders across our 6 focus geographics Australia (14), Canada (3), India (1), Netherlands (3), India (1), Netherlands (3), UK (7), US (1), Other developed country/cross-jurisdiction (1)

There are still huge challenges, however. Nearly half of justice senior leaders we spoke with and surveyed are dissatisfied with technology use for a reason. In the private sector, digital and digitally supported customer experiences are both widespread and sophisticated, as is the use of robotic process automation. And the emerging use of cognitive AI technologies at an enterprise level is increasing the focus on privacy, transparency and ethics, and corporate security. Those at the frontier of technological innovation are demonstrating to governments and service users what is possible – leaving them more frustrated by what governments offer.5 The progress developed in response to COVID-19 is also far from sufficient. As one NSW courts official put it, “There is still a while to go. It’s important to create a full scale end-to-end digital solution”… “we have swapped paper-based manual processes for electronic processes with manual workarounds, however, we need full digital solutions”… “we need to pick up the pace on digital transformation”. 6 Many highlighted that the big opportunity is not strictly about technology. True transformation will require a fundamental, end-to-end redesign of justice system processes to deliver better outcomes and better experiences – for victims, witnesses, the accused, and the families and professionals who support them.

Redesigning services in the twenty-first century almost always benefits from attention to enabling technologies. The justice system is about people and behaviour change, which technology can now assist. But it is also fundamentally about information, and technology is fundamental throughout the information lifecycle.

In this context, the risk is that leaders see continued innovation, enabled by technology and often working across organisational silos, as ‘too difficult’, despite its benefits. The pandemic saw people more willing to embrace proportionate risk (for example, recognising that the benefits of mobile phone access or remote contact with families outweighed security risks). But there is still danger of the return of risk aversion, not least because traditional solutions can still be partially effective against many problems. Yet, that effectiveness comes at the cost of forestalling further development: court backlogs can be somewhat alleviated through longer court opening times and increased staff, rather than virtual hearings and deep improvements in the efficiency of information sharing; prisons can reopen their visitor suites for (typically highly constrained) family contact and their classrooms for education, rather than embrace the benefits for wellbeing, behaviour in prison and recidivism generated through additional virtual visits and education opportunities. Community corrections and parole officers can reopen their offices and quickly fill their time with inperson contact, rather than pursuing a hybrid model of supervision and support that our interviewees generally viewed as far more successful. The risks of approaches that still feel ‘new’ to many are often all too visible, while the risks of inaction are hidden. When considering whether to maintain the increased use of virtual technologies in prison, for example, there has been anxiety about misuse of devices that prisoners have been given access to – but there is no comparable conversation about taking away visitation rights or cutting down staff numbers, despite the fact that contraband continues to enter some prisons through these routes on a daily basis. Without clear strategic commitment and leadership, it is therefore far from inevitable that the criminal justice systems’ use of technology catches up with other areas of public service and the private sector – rather than falling even further behind.

3. Deloitte justice leaders interviews, Canada, provincial Chief of Police, July-September 2020