Digital twins and virtual testing of regulatory remedies

Regulators in the UK and around the globe design and implement remedies to address their competition concerns. However:

- At present, the potential effectiveness of regulatory rules is not robustly tested before they are implemented.

- This increases the risk of remedies failing in achieving their objective, especially when they are focussed on digital markets: these markets are complex ecosystems where the underlying technologies are complicated and evolve very quickly.

- Digital twins provide a practical solution to this challenge.

The challenge: testing the effectiveness of regulatory remedies before implementation is difficult

At present, the potential effectiveness of regulatory remedies is not robustly tested before implementation. Although economic regulators undertake in-depth stakeholder consultations, these are neither an independent test of effectiveness (as they are subject to gaming) nor do they capture potential unknown pitfalls (as they are, by definition, unknown).

Instead, regulators test the effectiveness of their rules ex-post by analysing the competition and consumer outcomes in a sector. For example, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has an established programme of evaluating its merger remedies.

Recently, in some sectors, such as financial services, firms have started to use regulatory sandboxes to test their innovative propositions with real consumers in a controlled environment (see Financial Conduct Authority's Regulatory Sandbox).

The solution: building a digital twin of a regulated market

We use digital twin technology to assess the potential impact of proposed regulatory interventions on a market’s functioning and effectiveness.

We apply a two-step approach:

- In Step 1, we construct a conceptual model of the market ecosystem under consideration.

- In Step 2, we translate the conceptual model developed in Step 1 into a mathematical and computational model of the system aka a digital twin.

Our conceptual model assumes every relevant economic market is an ecosystem composed of many diverse, individual microscopic interacting parts (known as agents). Every economic market is made up of a myriad collection of these interacting agents which include suppliers, customers, consumers, government departments, regulatory bodies, investors etc. The focus of Step 1 is to create a detailed qualitative understanding of the different agents in the market, their key characteristics and the rules around their microscopic interactions with each other. In Step 2 we translate our qualitative picture of the system into precise mathematical and computational models which can then be used to conduct controlled, detailed numerical simulations of the systems behaviour.

The main advantages of our approach are as follows:

- We can include as many agents as we want. The only limit to the number of agents in our model is computational power.

- We can specify the behavioural characteristics of each individual agent (e.g. each individual supplier or consumer) and the rules of interaction between agents (these can be linear or non-linear, weak or strong, time dependent or independent etc).

- We can use machine learning and artificial intelligence to endow our agents with ever more complex behavioural heuristics.

Most importantly, the digital twin allows us to observe the emergent macroscopic behaviour which arises from the multitude of microscopic interactions between the individual agents which characterise the ecosystem. The emergent behaviour does not require us to make any assumptions about the system’s aggregate behaviour: it emerges naturally from the multitude of microscopic interactions between the agents.

Case study: digital twin of a digital market to test the design of the interoperability obligation

Platform interoperability is a key remedy in the European Commission’s (EC) Digital Markets Act (DMA) and is likely to be a key procompetitive intervention the UK’s CMA will use in the regulation of Big Tech. For example, when implemented, interoperability will allow new entrant social media platforms to interoperate with Facebook.

The DMA has already specified the requirements around how the Big Tech are expected to implement interoperability. We, therefore, asked ourselves two questions:

- Are the DMA’s specifications appropriate to deal with the competition concerns the EU identified?

- What could some of the unintended consequences be?

To test this we constructed a digital twin of a stylised digital market ecosystem with five platforms, a regulator and consumers (the agents). We then modelled consumer behaviour on the basis that they choose a platform based on its popularity and some other idiosyncratic factor (with a weighting of 60% to 40% respectively). The regulator intervenes in the market when a platform’s market share reaches 40%.

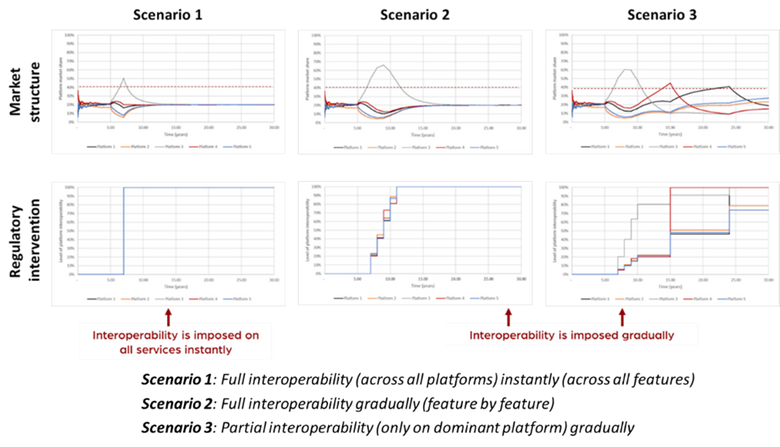

Our virtual experiments reveal the following as shown in the figure below:

- The actual implementation of the interoperability obligation can have a significant impact on how quickly new entrant platforms can gain market share (Scenario 1 vs Scenario 2). For example, in cases where interoperability is implemented gradually (as the DMA envisages), such a shift in market structure can take much longer than if interoperability is implemented from the outset.

- Under certain forms of implementation, even if the original platform lost its gatekeeper status, new gatekeepers can quickly emerge (Scenario 3). This is a risk we observe when only the gatekeeper is required to become interoperable with new entrant platforms.

- To design the right intervention, it is paramount for regulators to understand what platform characteristics (size, features etc) drive consumers’ choice. Our model assumes consumers choose a platform based on its popularity – however, should consumer preferences be driven by other factors (e.g. features) we are likely to get drastically different results. Hence, the design of the interoperability remedy would need to be adapted accordingly.

|

|

Conclusion

Our case study shows that digital twin applications can be a powerful method to test the effectiveness of regulatory remedies before implementation and help mitigate any potential unintended consequences.

If you would like to discuss our approach please send a message to Lara Stoimenova over LinkedIn.

Digital Twins updates

Sign-up to receive updates on techUK’s work around supporting the adoption of digital twin technology throughout our economy. You’ll receive regular insights, policy updates, event invitations and projects you can get involved with.

Smart Infrastructure and Systems updates

Sign-up to get the latest updates and opportunities from our Smart Infrastructure and Systems programme.