Online Safety and the Digital Services Act (DSA): An Overview

Seeking to foster safe online spaces for users, the Digital Services Act (DSA) sets out a comprehensive accountability and transparency regime for a variety of digital services and platforms operating in the European Union (EU). The legislation harmonises the diverging national rules of European Member States that had emerged under the E-Commerce Directive of 2000, and imposes obligations across a set of digital intermediaries, which include hosting services, caching services and online conduits, like social media platforms and marketplaces.

The DSA came into effect on 16 November 2022, and while certain aspects – such as the requirement to publish period transparency reports took effect immediately, the majority of the legislation's operational provisions will not be enforced until 17 February 2024. Complementing its sister legislations – the Digital Markets Act (DMA), the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and the proposed AI Act, the DSA is a key part of the European Union’s regulatory arsenal which seeks to comprehensively govern digital technologies in the region.

This article provides an overview of some of the key elements of the DSA, including its obligations for covered entities, special requirements for providers of Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Search Engines (VLOSEs), Independent Auditing provisions, and differences between the legislation and the UK’s Online Safety Bill.

Obligations and Intermediary Liability under the DSA

Touted to forge the global playbook on platform governance, the DSA introduces a series of obligations on its covered entities, that span requirements across content moderation, algorithmic transparency, trusted flaggers, targeted advertising and minor protection, among others. These stem from the DSA’s explicit intention to safeguard fundamental rights and ensure that platforms implement controls to assess and reasonably mitigate foreseeable systemic risks which may arise from the design, functioning and misuse of a platform’s interface (Recitals 80 – 83). In line with these objectives, the legislation also establishes the contours of what may constitute as illegal content, directing covered entities to take preventative action to mitigate their prevalence online.

The DSA maintains intermediary liability or 'safe harbour' provisions for all covered services. This provision, previously established under the EU’s E-Commerce Directive, ensures that providers are not held responsible for the content hosted on their platforms as long as they are unaware of its illegality or infringement. Furthermore, if providers become aware of the existence of such content on their platforms, they are required to promptly remove or block access to it to maintain their protection from liability. This is notable, in that it contrasts parallel regulatory efforts in jurisdictions like the United States, Canada and India – which are currently seeking to weaken, or even remove safe harbour protections for online platforms.

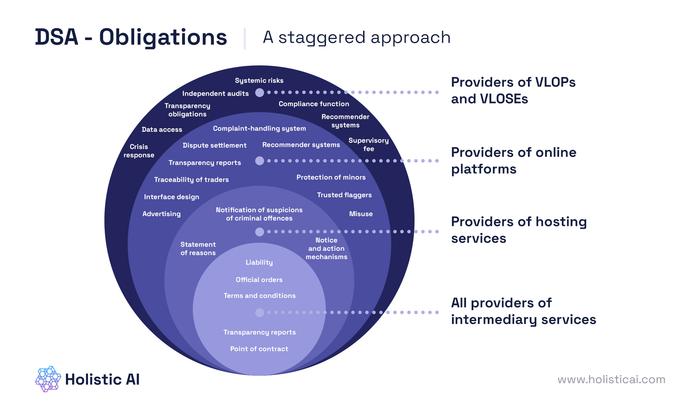

Taking a staggered approach, the DSA imposes cumulative obligations (Chapter III) on intermediary services that fall under the definition of Hosting Services, Online Platforms and Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Search Engines (VLOSEs). The provisions apply differently depending on the nature of the intermediary service, with VLOPs and VLOSEs subject to the most stringent requirements. The following diagram illustrates the many obligations for covered digital services under the DSA.

VLOPs and VLOSEs

Perhaps the most significant component of the DSA are its requirements for VLOPs and VLOSEs. These entities are defined as online platforms with a minimum of 45 million active users per month. On April 25, 2023, the European Commission designated 17 VLOPs and 2 VLOSEs, encompassing a broad spectrum of social media, search engines, app stores, and e-commerce platforms. In addition to complying with general due diligence requirements applicable to all intermediary services, these 19 platforms will be subjected to a comprehensive set of special obligations outlined in Articles 34 to 48 of the DSA. VLOPs and VLOSEs will have to comply with these requirements before the 2024 deadline, with the first risk assessment report under Article 34 due in late August 2023.

The DSA introduces a set of novel regulatory tools to meet these requirements, ranging from mandatory algorithmic transparency, giving users the option to opt out from personalised recommendations, to providing vetted researchers and authorities access to platform data and mandating annual independent audits. Designating VLOPs and VLOSEs has been a contentious topic, with e-commerce platforms like Zalando disputing their inclusion in the list and even filing legal action against the same in the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

Independent Auditing under the Digital Services Act

The auditing requirement provided under Article 37 of the DSA is particularly noteworthy, as it requires VLOPs and VLOSEs to commission external auditors to validate their compliance with due diligence commitments in the form of an Audit Report submitted to the Commission on an annual basis. A global first, procedures of conducting these have been outlined through a delegated regulation published by the Commission on 6 May 2023, which is currently at draft stage. Mostly containing implementational guidance, the draft rules also mention the need to develop auditing methodologies for algorithmic systems, which include advertising systems, recommendation engines, content moderation technologies and features using generative models.

Given the novelty of this regulatory initiative, there currently exists little clarity and consensus on criteria and standards required for conducting such audits. For instance, the DSA does not explicitly outline criteria for procedural assurance, and neither the draft rules nor the DSA provide alternative sources or identification of criteria for the same purpose. Similarly, the draft rules do not specify an assurance standard for the same. These discrepancies and others have been communicated by various stakeholders to the Commission through the Public Comments process, with the hope that relevant guidance is provided in subsequent iterations of the delegated regulation, and through the establishment of standards under Article 44 of the DSA.

It is also important to mention that these audits are quite different from those mentioned in the EU AI Act, as the latter only applies to providers and deployers of High-Risk AI Systems (HRAIS) spanning across sectors (biometrics, critical infrastructure, HRTech, Insurance, etc). Further, DSA Audits are geared towards providing third-party assurance on online safety platform requirements, while AI Act audits will focus on providing assurance on Quality Management Systems established by providers and deployers of HRAIS. While there are overlaps in both regulations on governing algorithmic applications like recommendation systems, these commonalities are envisioned to complement each other in achieving user safety, platform accountability and AI trust objectives.

Key Differences between the DSA and the UK’s Online Safety Bill (OSB)

While both legislations are geared towards safeguarding online environments, they vary in their scope, approach and nature of enforcement. The OSB for example, divides services into different categories depending on their size and deemed risk, as opposed to the DSA’s focus on digital intermediaries, which include a wide variety of social media, search engines, online marketplaces and cloud services. Further, while the DSA treats all kinds of illegal content equally, the OSB contains different obligations for different types of illegal content. The nature of risk assessment obligations is also different; only VLOPs and VLOSEs need to comply with these requirements under the DSA, as opposed to all services under the OSB’s ambit. Finally, the DSA will be enforced by the EU Commission and Digital Services Coordinators – government entities – while the OSB will be enforced by Ofcom, the UK’s independent communications regulator.

What’s Ahead

Differences aside, both regimes bear extra-territorial influence, will have global implications on regulatory compliance, and are actively committed towards enhancing regulatory cooperation and harmonisation on enforcing online safety. Invariably, businesses operating in both regions will have to keep abreast of these regulations and implement necessary controls to best comply with them, where applicable.

For more information, please contact: